Consumer demand was the driving force behind the regulation that was implemented on January 1st of this year. A “Product of Canada” label now means that 98% of the product’s contents were grown in Canada. Last year, 50% of the cost of production was enough – and packaging is where most of the cost is incurred. How many Canadians does it take to realize that the pineapple inside of that can was not grown in Canada, despite the label? Not that many. But how many Canadians does it take to complain about it, before that label is corrected? Quite a few, and it has certainly taken a while. Now that enough consumers have complained however, changes have been made, and guess who is said to be complaining now? The farmers.

Laurent Pellerin, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, reported CBC News yesterday that if 85% of the product was grown in Canada, that would be sufficient. It is unclear on whose behalf she was speaking, however farmers are now being blamed for nonchalance towards specification as to the exact percentage of Canadian-made ingredients in a product. Consumers, expressing their opinions on the CBC website, appear to be disgusted at the prospect of farmers shrugging their shoulders and saying that 85% would be sufficient. Consumers are demanding that exact percentages are given, as well as details as to where the non-Canadian ingredients come from. Wrote one consumer in the section for posting comments: “When you buy something without peanuts, are you satisfied with ‘No Peanuts’ meaning 85% peanut-free? No, of course not.”

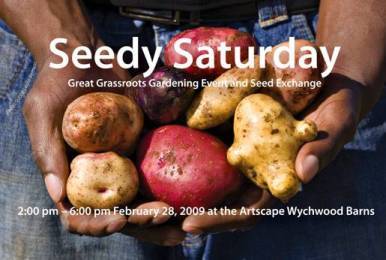

"Product of Canada" now means that 98% of the ingredients were grown in Canada.

It is all quite complicated. Some producers are objecting to the label because they are now excluded due to a mere 3% of non-Canadian ingredients. Some consumers are blaming Paul Mulroney for the issues that have resulted from his free trade policies. Others are saying, “what’s the big deal? 85% is better than what we’ve had in the past.” There are farmers who are responding to that opinion with a resounding “damned right” and still other farmers who are saying, “heck no! 100% Canadian or GO HOME.”

I find it ironic though, that the main reason consumers demanded the label in the first place was for the benefit of farmers, and in order to support Canadian growers and more locally produced food. And now farmers are being pin-pointed by reporters as the ones who are reacting against the strictness of this label. Riddle me that. I would venture to say that reporters and responding consumers are betting on the wrong horses. It is likely that the ones who will be missing out as a result of this label are the large corporations that import a lot and process a lot. Sodium! Refined sugar! How often are nutritionists warning against the consumption of too much sugar and salt? Eliminating these will present big problems for those processors who like to add a little wee bit of fruit to that “fruit cup” and a little wee bit of tomato to that “tomato soup.” It makes for a tasty product, hooks a lot of kids and adults alike, and can sit on the shelf for months; no, years!

The new guidelines for the “Product of Canada” label means that we are going to have to get a little more creative in order to keep certain products eligible. And this will to the benefit of the Canadian farmer. We can choose to see it as an opportunity for Canadian farmers to shine, and as an occasion to explore the potential of Canadian land to produce perfectly sufficient diets. As many consumers have testified – while proclaiming that even 98% Canadian is not enough – it is possible to consume a purely Canadian diet, and the “Product of Canada” label can make it a little easier to do so.

Maple Syrup - 100% Canadian